12:00 PM

May 18

12:00 PM

May 18

02:30 PM

May 18

12:00 PM

May 19

02:30 PM

May 19

03:00 PM

May 24

05:30 PM

May 24

© 2024 USA Lacrosse. All Rights Reserved.

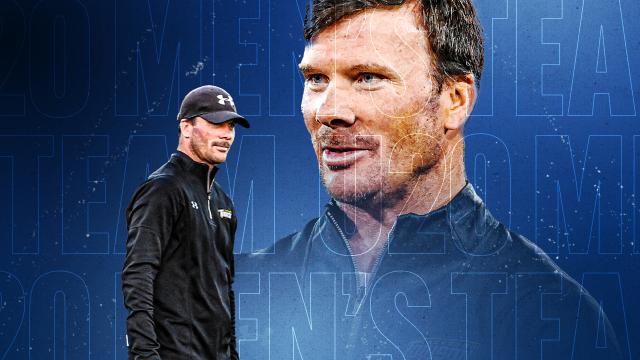

Few possess the stamina to go toe-to-toe with John Danowski in a charm offensive.

But Leslie Basler had the U.S. men’s national team coach cornered. Sitting in a blue plastic Adirondack chair outside the coaching staff’s quarters in the dimly lit courtyard of the Shefayim kibbutz in Herzliya, Israel, Danowski peppered Basler, the wife of then-USA Lacrosse national teams general manager Lance Basler, with a series of icebreakers.

It was classic Danowski. Dispense with the small talk. What’s the last book you read?

Basler, a bit punchy perhaps following the 11-hour flight from New York to Tel Aviv, quickly turned the tables in the parlor game. “What was your favorite part of the tour today?” she asked.

Danowski didn’t flinch.

“The look on Mike Ehrhardt’s face when he walked out of the tomb of Jesus Christ at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre,” he said.

What a sight it was earlier that day in Jerusalem to see Michael Ehrhardt, this 6-foot-5 colossus, reduced nearly to the point of tears as he exited the stone shrine through a tiny archway guarded by an Orthodox priest — an emergence that seemed all too symbolic two nights later when Ehrhardt sent Lyle Thompson’s stick flying like a propeller into the sky in the 2018 world championship opener at Netanya Stadium.

The U.S. defeated the Iroquois Nationals 17-9, the first of seven wins in 10 days culminating in a dramatic last-second victory over Canada in that same stadium. For the 10th time in its storied history, the U.S. won the gold medal.

And for just the second time in world championship history, a defensive player won MVP.

It was Ehrhardt, the long-stick midfielder who at age 26 transformed into one of the best players on the planet. Equipment manufacturers soon came calling with endorsement offers. Ehrhardt’s ascendancy coincided with the advent of the Premier Lacrosse League, which promised unprecedented exposure for its athletes.

Four years in a row now, Ehrhardt has been named the PLL Brodie Merrill Long-Stick Midfielder of the Year — an award named after perhaps the only other player ever to possess his same blend of size, physicality, athleticism and stick skills off the ground.

“Those two weeks in Israel, that’s where everything changed in his lacrosse career,” said Lindsey Ehrhardt, his younger sister and a former All-American defender at Loyola. “Leading up to it, the changes he made — the nutrition, working out, all of it. He really bought into the idea of playing on the U.S. team. We’ve never actually talked about this, but from my perspective just knowing him, it’s the pride that he feels in terms of honor, country and family. When he’s representing something, he’s all in.”

The more you get to know the Ehrhardt family, the harder it becomes to avoid the classic tropes of Americana. Dad was the star quarterback. Mom was the head cheerleader. “If you promise not to write that,” Tom Ehrhardt quipped. Too late.

They grew up half a mile apart in Flushing, New York, a Queens neighborhood about 10 miles east of Manhattan. Tom Ehrhardt went to Holy Cross, an all-boys high school. Diane Ficcara went to St. Agnes, an all-girls high school. Both Catholic. Their circle of friends remains intact today.

“Everyone on our side knows the story,” he said. “That’s the heart of it, man.”

Tom Ehrhardt was a 6-foot-3 gunslinger of a quarterback who starred at C.W. Post and then Rhode Island, setting numerous national passing records in 1985. He threw a perfect ball. “A spiral on the money,” his top receiver at URI, Dameon Reilly, told the New York Times back then. He signed as an undrafted free agent with the New York Jets and spent time in Cincinnati Bengals training camp as Boomer Esiason's backup.

These are the genes Michael Ehrhardt inherited. His older sister, Lauren, found lacrosse first. The Nassau County town they grew up in — Westbury, New York — offered the sport for girls but not boys. She went on to win an NCAA Division III championship as an attacker at Franklin & Marshall. After Michael came Brian, who flourished in basketball, then Lindsey. All of them played multiple sports.

“A sick wide receiver in football. Ridiculous,” said Brendan Fowler, Ehrhardt’s football and lacrosse classmate at Chaminade High School. They would reunite years later as teammates with Major League Lacrosse’s Charlotte Hounds. “He would’ve been the guy that goes to play at an FCS school and goes on to play in the NFL. He’d be an Adam Thielen.”

The family rule was no football until middle school, however. That’s how Ehrhardt got into lacrosse. His cousins, Bobby and Kevin, introduced him to the sport when he was in fourth grade. They played for the PAL program in Mineola, the next town over. Lacrosse fed Ehrhardt’s appetite for movement — he still gets stir-crazy after just an hour or two lounging on the beach — and knocking kids around.

“I loved it,” Ehrhardt said.

By the time Ehrhardt was a freshman at Chaminade, an all-boys school and national lacrosse powerhouse, he had grown to 6-foot-3 but topped out at 175 pounds. “There wasn’t much to me in high school,” he said. “I was a toothpick.”

Flyers coach Jack Moran saw Ehrhardt’s length, however, and converted him from an offensive midfielder to a defenseman. He did not start as a freshman.

“He got exponentially better,” Fowler said. “He came in as a second- or third-line middie. They gave him a pole. Three years later he’s the best defenseman in the country.”

When Ehrhardt took his official visit to Maryland, then-Terps coach Dave Cottle looked at his build and saw the potential. “Oh man,” Cottle told him. “We could put some weight on you.”

Ehrhardt had the right work ethic to maximize his obvious physical aptitude. He got that from his family, too. His grandfather on his mother’s side was a carpenter and avid marathoner. His grandmother on his father’s side raised seven children by herself after she became a widow at age 43. She had an eighth child who died of meningitis at just two weeks old.

“My dad's probably the way he is because of that,” Ehrhardt said. “It took me a little bit to learn what makes his drive. He’s been my biggest role model and someone I’ve tried to resemble.”

Ehrhardt’s grandmothers, Ann Ficarra, 84, and Betty Ehrhardt, 96, mean just as much to him. They assemble with relatives every weekend in Westbury to watch his PLL games on TV.

“The sense of family, the sense of loyalty, the sense of pride, the sense of love — when we feel it, we feel it deep,” Lindsey Ehrhardt said.

Ehrhardt never got to play for Cottle. The coach who once led Loyola to the NCAA championship game was fired after nine seasons at Maryland following a final four-or-bust campaign in 2010.

Cottle’s successor, John Tillman, had recruited Ehrhardt to Harvard. His defensive coordinator, Kevin Warne, was coming with him to Maryland. Tillman’s emphasis on family and his vision for the Terps resonated with Ehrhardt, as did the opportunity to play for Warne, one of the best defensive coaches in college lacrosse.

Besides, Ehrhardt was not the type to back out of a commitment. When Maryland ended a 42-year national championship drought in 2017, Tillman credited Ehrhardt and his classmates for laying the foundation with consecutive championship game appearances in 2011 and 2012 and a final four run when Ehrhardt was a senior captain in 2014.

A two-time All-American, Ehrhardt still regrets not getting Maryland over the hump during his time there. “It’s just something I wish we accomplished,” he said. “We had some challenges throughout the year to make it the program that it is.”

Just how good were those Terps teams that fell just short? Thirteen players who suited up with Ehrhardt in College Park were his teammates when they won the inaugural PLL championship with the Whipsnakes in 2019.

“It’s such an incredible high. Running around celebrating with your teammates. Being in that locker room. Nothing compares being out in the real world,” Ehrhardt said. “You want to bottle it up.”

Ehrhardt chased that feeling for four years at Maryland and another four years as a pro with the Hounds to no avail going into tryouts for the 2018 U.S. men’s national team. In addition to his defensive prowess, he began to establish himself as an offensive threat in the transition game. Ehrhardt registered 30 points in his final two seasons with Charlotte.

Tony Resch, an assistant coach for both the Hounds and the U.S. team at the time, lobbied to get Ehrhardt in the Team USA pipeline. Which was why he was surprised to see the dynamic long-stick midfielder planted down low during evaluations at USA Lacrosse.

Ehrhardt figured he had a better shot of making the team as a close defenseman, what with Kyle Hartzell, Scott Ratliff and Joel White taking turns up top.

“You just couldn’t feel him the same way there,” Resch said. “The guys down low, sometimes they don’t get tested all that often. When you get guys up top, you can feel their impact a little bit. I said to Mike, ‘You need to go and play some pole also.’”

Ehrhardt took Resch’s advice and the rest of the coaching staff took notice. Ever the whisperer, Resch said he gets too much credit for Ehrhardt’s emergence.

“It kind of snuck up on me over time. He’s really good,” Resch said. “He just kept building his game. Eventually he was controlling the middle of the field, transitioning to offense, playing really good defense, getting ground balls on faceoffs or in our end. Suddenly, it was, ‘Wow, he is a force.’”

In the real world, Ehrhardt’s VP stands for vice president, a title he holds at First Nationwide Title Agency in Manhattan. He procures new business and ensures there are no surprises when it comes time to close a commercial real estate deal.

Wining and dining clients, Ehrhardt, who lives in the West Village, was up to 235 pounds by the time he made the U.S. team in January 2018. Preparing to play in the Middle East climate, he committed to 5:30 a.m. field workouts and a Whole30 eating program limited to high-quality meat, protein, vegetables, fruits, nuts, seeds and fats. No sugar. No grain. No dairy. No alcohol.

Fowler, who also works in New York City as a financial analyst, met with a high school friend who mentioned he saw Ehrhardt at a Barry’s fitness studio. During the treadmill portion of their high intensity interval training, they were supposed to start at 6 mph and gradually get to 10 mph. Ehrhardt started at 10 and went up from there.

“This is embarrassing,” the friend said. “I’m not working out with Ehrhardt anymore.”

Ehrhardt lost 20 pounds but somehow got stronger. “I think he moves better when he’s a little lighter,” Tom Ehrhardt said. “He likes playing heavier because of the physical grind and muscling people. Going into those games, he was probably the lightest he’s ever been.”

Ehrhardt’s breakthrough performance in Israel — ranking second on the U.S. team with 26 ground balls, neutralizing opponents’ most dangerous initiators, stabilizing wing play for a dominant faceoff unit and scoring a pair of goals in a world championship semifinal win over Australia — led to endorsement deals with STX and then New Balance. The PLL also reenergized him, although he joked that the league probably regrets putting so many Maryland players together on the Whipsnakes.

“He’s an attacking defender,” said Lindsey Ehrhardt, who credited her own breakthrough at Loyola the next year to mimicking her brother. “Typically on defense, you’re on your line and your goal is to not let them break that barrier. However, with Michael, he doesn’t even wait for attackers to let that be an option. He goes out and he disrupts.”

Now at the dawn of another U.S. cycle, Ehrhardt, 30, no longer has the look of a wide-eyed rookie but rather that of a grizzled veteran. His once jet-black hair has a little more salt, a little less pepper. He got engaged over the summer. He speaks wistfully of the good old days, when recruits still received letters rather than texts on Sept. 1 of their junior year and when you could look up into the stands during a Chaminade-St. Anthony’s game and see college coaches evaluating players in an environment that actually meant something.

During training camp in September, he led teambuilding activities at the hotel and distributed Gatorade squeeze bottles to the defensive players during breaks. He spoke of 2023 as if it might be his last hurrah, a somewhat shocking revelation from a player who is very much in his prime.

Ehrhardt is one of seven players from the 2018 U.S. team on the current training roster. Trevor Baptiste, Jesse Bernhardt, Marcus Holman, Jack Kelly, Rob Pannell and Tom Schreiber are the others. They're trying to recapture the chemistry that made Israel so special.

“I don’t think I’ve cried like that before or since,” Tom Ehrhardt said of the tearful embrace he shared with his son in Netanya Stadium after he received his gold medal and MVP trophy. “The culmination of everything.”

Matt DaSilva is the editor in chief of USA Lacrosse Magazine. He played LSM at Sachem (N.Y.) and for the club team at Delaware. Somewhere on the dark web resides a GIF of him getting beat for the game-winning goal in the 2002 NCLL final.